Mechanism design

3/14/24 (happy pi day)

I am ridiculously caffeinated right now and have been spending my time - and by time I mean from 6pm-10pm on a Wednesday and 10:22am - 5pm on a Thursday - here - watching Jeff Ely of Northwestern to try and give a shot at passing a midterm worth 40% of my grade.

Who knows if I’ll pass. But I’ve spent about 10.5 hours of my life thinking about mechanism design and social choice problems so I thought I’d write about it.

This class is called intro to mathematical economics, which gave me nothing. Turns out it’s a mechanism design theory course with a bunch of math. They need to rename it.

Anyway, here's a shot at explaining it.

If I go into what economics actually is, I’ll end up going down a rabbit hole of history and coming to the conclusion that there’s no widely accepted

definition of economics (like any subject). Take computer science. What’s the science? What is a

computer? At what point does something stop being a computer? And is it really the study of computers

or more so just applied math using computers? And math, my god, probably has the most beautiful/poetic

set of definitions of all - “All is number. Number rules the universe," Pythogoras said. Everything - this screen, audio files, coffee cups, napkins, can be expressed using math - just with different measurements or my fave, 0s and 1s.

Here are some definitions though:

1. Lionel Robbins: “the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.”

2. Adam Smith: “the science of wealth.”

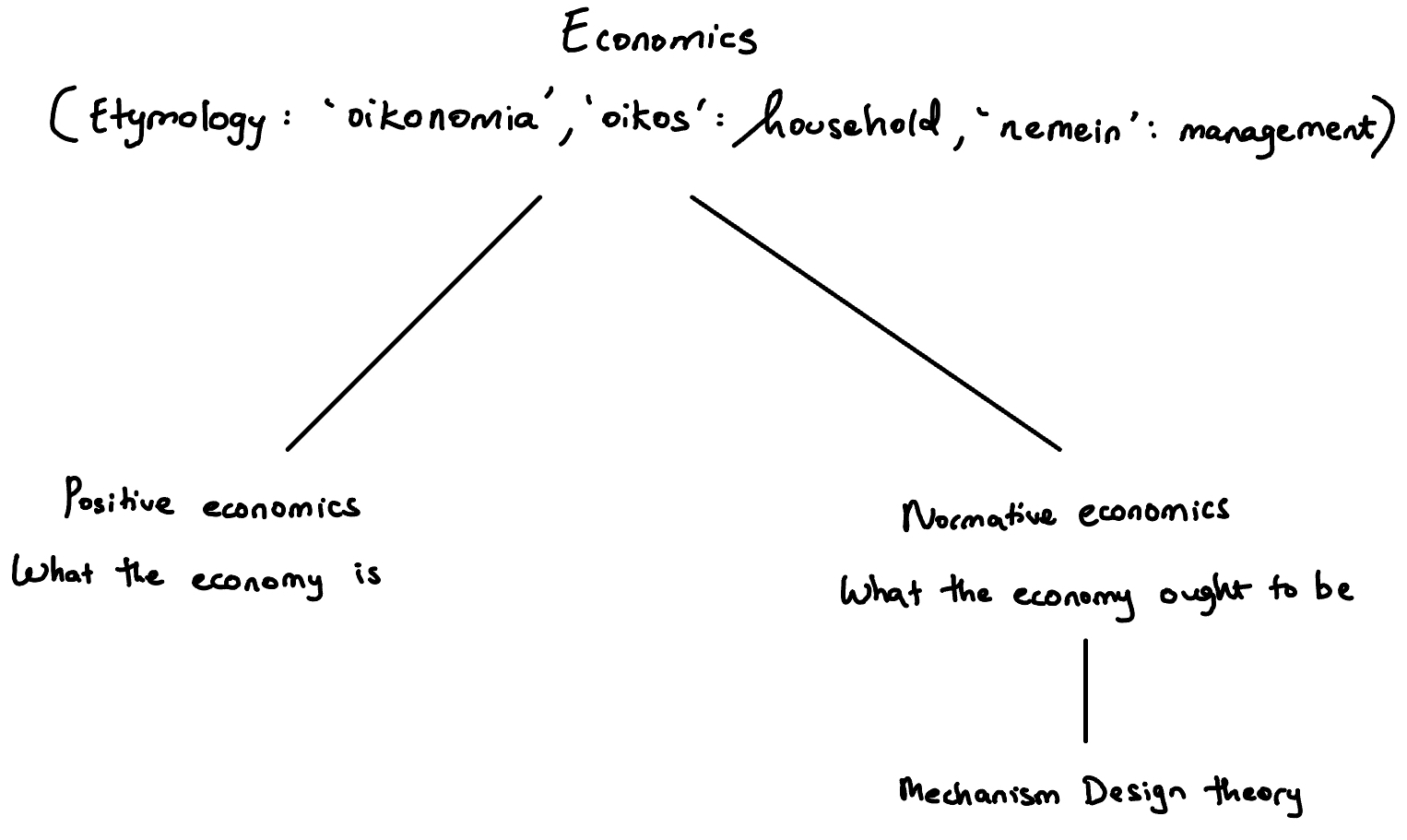

Regardless of a standard definition, for simplicity, I understand it as the study of human choices and their outcomes. It has two branches: positive economics, which focuses on what the economy is, and normative economics, which focuses on what the economy should be. This is where mechanism design comes in.

Ok fantastic, now to this course.

Here’s our problem:

We have a good. We wanna give it to someone. There are several people who want it. Our goal is to give it to the person who wants it the most. How do we do that?

My first reaction is to make ‘em compete in some challenge. Winner takes the good. But that doesn’t ensure that the winner wanted the good the most - it just means they won the challenge. So this mechanism fails. Let’s call this mechanism 1.

Mechanism 2:

Just ask them how much they value the good. Give it to the person with the most value. Reasonable, but fails because how do we know they’re telling the truth? They have an incentive to exaggerate their value to get the good, so it’s not guaranteed that it’ll go to the person who truly values it the most.

Mechanism 3:

Alright um, so we don’t want them to exaggerate, let’s then set up a bidding system. We’ll give each person a paper and tell them to write down how much they’re willing to pay and then make them put their money where their mouth is, i.e. they need to pay the amount they wrote down. Great, but here’s the thing, they’re likely to underreport. Say I was told to put down how much I would pay for a cup of coffee, and I valued it to be worth five dollars. If I put down five dollars on the paper and end up winning, my satisfaction is nil. And in economic or mathematical terms, my net benefit is 0. So I’ll probably put down something less than 5, say 4 dollars, and if I win I’ll get the coffee and a $1 profit. So this fails too… we need to get them to tell the truth.

I wanna pause here and say, what a cool problem. Econ is busy trying to design a system to get the participants to tell the truth. All of this assumes that humans know what truth is, which is a wonderfully thorny subject, what their truth is, and that humans are rational beings (no). I doubt most or all of those assumptions are true, but then again, what is the truth? Let’s just simplify our lives and assume there is a truth, each human knows their own truth, and they are going to act rationally.

Alright here’s the bread and butter blow-your-mind solution to this problem. This guy, or more like Nobel laureate William Vickrey, came up with it.

Mechanism 4:

Ask everyone to write their value on a piece of paper, but tell them that the winner will not pay their own bid, but the second highest one. OKayyyy, soooo our first problem was participants exaggerating their price. They won’t do that now because if the second highest bid is greater than their true value, then they can’t pay it. Our second problem was underreporting their price. They won’t do that now either because it’s basically guaranteed that the winner will receive some positive net benefit since they’re not paying their own price. And, there’s risks to underbidding - they might lose the good. So their dominant strategy (game theory speak) is to tell the truth. Fanfuckingtastic.

This is pretty much the core of the class. The rest of this is gonna go in the weeds a bit. Here’s more of a highlight reel of results.

Welfare economics

(Jesus christ there are so many subfields and sub-branches of econ - micro, macro, positive, normative, welfare, managerial etc.)The goal of welfare economics, courtesy Jeff Ely, is devising a standard to judge economic outcomes as good or bad.

The question is, given a group of people with different preferences about a decision, how do we make an aggregate decision for all of the people in the economy? Well we can make any decision really, but let’s base it off of three principles.

If everyone thinks one choice is better than another, then our ranking of the choices should reflect that. If our group is, say, a class of third graders, and everyone believes that chocolate milk is better than regular milk, they should get chocolate milk. However, unanimity is kinda rare. This is called the Pareto principle and it’s named after a fantastically-named Italian dude, Vilfredo Pareto.

No dictatorships. If one third grader named Fred believes that normal milk is better than chocolate milk, and our decision is based only on what Fred thinks, Fred’s a dictator! We can’t have Fred make the decision for everyone. (This milk example is probably because I’ve developed lactose intolerance and miss milk every day.)

Lastly, the rankings of two alternatives should not depend on a third. Say we conclude that chocolate milk is in fact better than regular milk. Then we introduce soy milk to the mix and now the rankings become from worst to best, chocolate milk, soy milk, regular milk. The addition of soy milk switched up the ranks of chocolate and regular milk, making their rank dependent on it. This can’t happen! Formally this is called independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA).

There’s two more prof Ely didn’t talk about:

Universal Domain: Voting must account for everyone’s preferences.

Social Ordering: Each individual should be able to order the choices in any way and indicate ties.

I gotta be honest I don’t totally understand universal domain and social ordering, but there they are.

Now now now, here is la catch - Nobel laureate Kenneth Arrow proved that IT IS A MATHEMATICAL IMPOSSIBILITY to make an aggregate decision that fulfills all these principles. And he proved it while he was a grad student which just makes it cooler.

Formally, Arrow’s Theorem: suppose there are more than two alternative choices. Then no social welfare function satisfies universal domain, social ordering, pareto efficiency, no dictatorship, and IIA. See more here. We could just end the conversation here. But instead we adaptable humans agree to drop a principle. So we drop universal domain and instead say that our social welfare function (SWF) only applies in situations where there’s a valid measure of welfare. In this class, that measure is money or someone’s maximum willingness to pay (WTP).

Two definitions coming your way:

Utilitarianism is finding the outcome that maximizes social value.

An outcome is Pareto efficient (also named after Italian dude Vilfredo Pareto) if there’s no other outcome that everyone believes is better.

An outcome may not be both utilitarian and pareto efficient, but here’s a dandy result: when monetary transfers are possible, i.e. when money is involved, the utilitarian and pareto efficient outcome is the same.

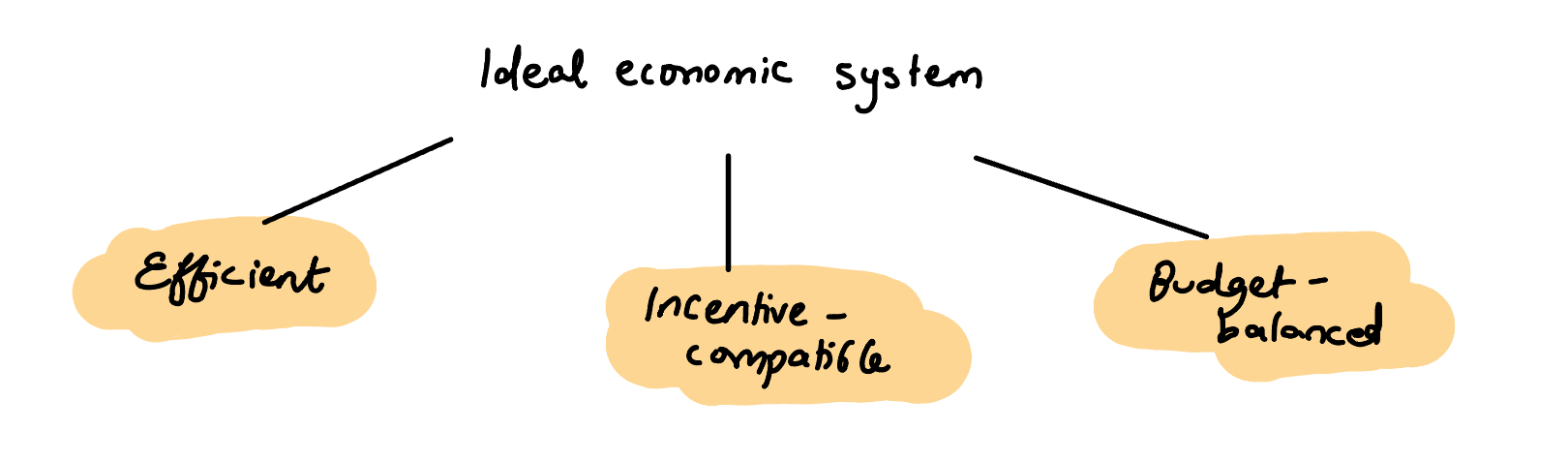

An ideal economic system is efficient, ensures that everyone in it tells the truth (incentive compatible), and is budget-balanced i.e. the amount of money buyers pay equals the sellers' costs.

Yet here’s another one of those Arrow’s-theorem-esque-showstopper-but-also-disappointing results: there’s no one mechanism that can solve all those problems.

There’s always a tradeoff between efficiency and incentives in the world. So we come to the conclusion that there’s no way to efficiently provide public goods. Sad.

What about private goods? Here’s where markets come in and the result is pretty sweet.

In a market, there are buyers and sellers. Let’s establish that any trade between a buyer and a seller is efficient only when the buyer’s willingness to pay exceeds the seller’s opportunity cost.

Yet here’s the issue with lying humans: the incentive problem. The seller is incentivized to overreport their opportunity cost and the buyer is incentivized to underreport their willingness to pay.

Problem: How can we extract the TRUTH? How can we extract the buyer’s true WTP and the seller’s true OC?

In order for the buyer to truthfully tell us their WTP, their payment cannot depend on what they state as their WTP. There’s a pattern here. In order for humans to tell the truth, the action they are expected to take should not be aligned with their truth. You can’t make people put their money where their mouth is. They won’t. Solid.

The price that the buyer pays and the seller receives has to be independent of the buyer’s WTP and the seller’s opportunity cost.

Turns out market forces do this. Result: the institution that solves this problem is a market.

The mechanism:

Market forces set the price at which trade happens. Just have each buyer and seller say yes or no to the price

It’s inefficient though, because it may be that the buyer’s WTP is greater than the seller’s OC but less than the price fixed by the market, but it’s the best we can do.

So we just said that markets are kinda inefficient, which goes against poor Adam Smith and his the invisible hand ideal, another super cool concept that says that self interested people will act for the public interest in a free market.

But, we’re gonna see that competitive markets (THAT’S RIGHT, GOOD OL’ COMPETITION) bring us closer and closer to the invisible hand ideal.

A thin market exacerbates incentive or truth-telling problems. Competition among buyers and sellers can help with the incentive problem, so a thick market has more trade and will incentivize folks to tell the truth. So again, more competition is good for da economy. Swag we just built up to the shit they teach as a fundamental in an intro to econ class.

Here’s the mechanism (formally):

1. Allow all buyers to announce their values and all sellers to announce their costs.

2. See how many units can be sold by counting how many buyers’ values are above the opportunity cost of some seller.

3. That’s the number we’d like to sell exactly so that the market clears. But we’re gonna sell one unit less than that.

4. So if we can trade m + 1 units, we’re going to sell m units. Now how are we going to determine the price for these m units?

5. Find the buyer whose WTP is m + 1st highest WTP. That’s the price. We’ve solved the incentive problem of buyers.

6. All sellers will receive the m + 1st lowest cost. We’ve solved the incentive problem of sellers.

This entire mechanism has just 1 unit of inefficiency, namely the m + 1st unit we didn’t sell. But in the long scope of things, that doesn’t really matter that much.

Alright that's it for now. I'll write more if I actually understand the class more.